MOSA in defense acquisition: challenges, solutions, and a model

StoryOctober 10, 2025

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) is adopting a modular open systems approach (MOSA) to keep pace with rapidly evolving threats. MOSA creates long-term value by making systems easier to upgrade, maintain, and integrate. Its success will depend on clear standards, robust cybersecurity, and cultural shifts in acquisition practices. It has the potential to deliver rapid technological upgrades and improved interoperability to those who need it on the battlefield.

The modern battlefield evolves much faster than current defense acquisition programs, as weapon systems become increasingly complex, interconnected and costly. The Fiscal Year 2021 (FY2021) National Defense Authorization Act mandates a modular open systems approach (MOSA) implementation to “the maximum extent practicable” to make weapon systems more flexible, upgradable, and cost-effective over their life cycle. Beyond just a design philosophy, MOSA is a deliberate technical and operations strategy to create more sustainable defense acquisition programs.

Technically, MOSA ensures that defense systems – from physical weapons to digital networks – are easier to develop, maintain, and upgrade. Systems designed with modular architectures are less likely to become obsolete because they provide the flexibility needed to integrate new capabilities as they emerge without needing to redesign the entire system.

From an operational perspective, MOSA enables the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) to acquire modules – the system’s components – from multiple vendors, enhancing competition and reducing costs over the system’s life cycle. With open competition for individual components, MOSA encourages vendors to innovate and reduces the DoD’s dependence on legacy suppliers. Furthermore, as MOSA leverages universal standards it improves interoperability while saving cost because components can be reused across platforms and programs.

Together, these technical and operational benefits accelerate acquisition programs, which is essential for DoD to maintain technological superiority in the face of evolving threats.

While the intentions driving MOSA are admirable, achieving true MOSA across the entire DoD is proving to be much easier said than done. To attain MOSA at scale, the DoD must first clarify and formalize its standards.

Key considerations for MOSA standards

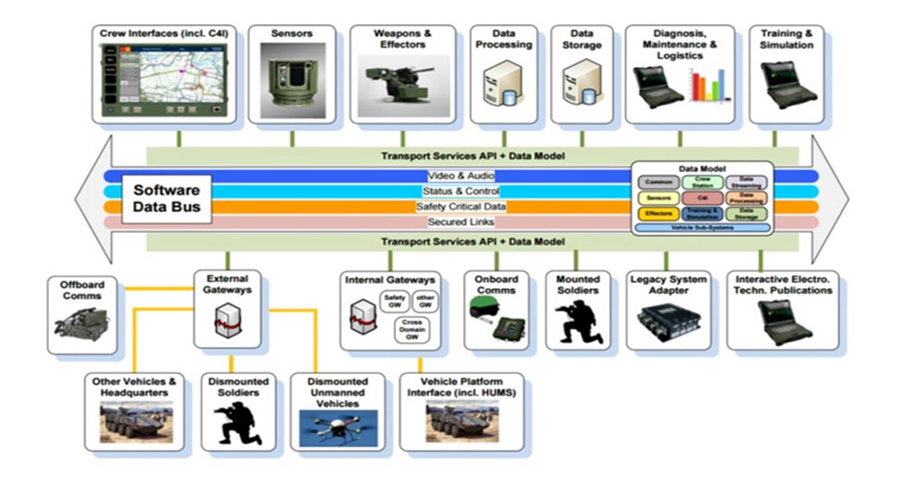

At its core, MOSA enables defense systems to be modular, loosely coupled, and highly cohesive, similar to the concept of “plug-and-play” components in commercial computing. A weapon system designed with MOSA principles consists of components – such as engines, sensors, and software modules – connected through well-defined interfaces that adhere to universal standards. One such standard is the U.S. Army’s VICTORY [Vehicle Integration for C4ISR/EW Interoperability].

VICTORY is specifically designed to modernize ground-vehicle networks. By replacing point-to-point cabling with a shared, Ethernet-based architecture and using standards like time-sensitive networking (TSN), VICTORY enables different mission systems to share data and resources more efficiently.

Figure 1 shows VICTORY’s basic tenets, including proving architecture compliance via testing, identifying a roadmap from current to future architectures, and treating information assurance as essential.

[Figure 1 ǀ Shown are the key components of ground vehicle MOSA standards.]

These standards detail a network-based architecture for integrating electronic systems on ground vehicles. They aim to support a full spectrum of platform functionality, from simple, low-functionality platforms to highly sophisticated ones. Moreover, they’re intentionally designed to strike a balance between allowing subsystems to interoperate as necessary, while simultaneously empowering manufacturers to propose novel implementations.

MOSA interfaces at large can encompass physical connections, power requirements, data protocols, and communication methods. Importantly, not all interfaces in a system need to be open. MOSA standards like VICTORY should focus on key interfaces that are likely to change, fail, or require interoperability.

By isolating functionality into modules and standardizing critical interfaces, MOSA can meet its key goal: allowing components to be easily added, replaced, or upgraded without redesigning the entire system.

MOSA: Easier said than done

Even with well-defined standards, transitioning to MOSA presents significant challenges. For one, open interfaces can introduce cybersecurity risks. If they’re not properly secured, these interfaces may allow unauthorized access to classified systems or data. It’s essential to implement robust cybersecurity measures, including authentication, encryption, and continuous monitoring, to prevent potential exploitation.

In addition to introducing cyber vulnerabilities, the transition to MOSA requires significant upfront investment. While MOSA has long-term cost-saving benefits, applying MOSA to existing legacy systems can be expensive, often demanding extensive engineering work and acquisition of interface data rights. Requirements like open standards licenses, digital engineering tools, and personnel trained in modular architectures are costly, both in terms of time and funding. With countless competing priorities, these initial investments can seem overwhelming.

Beyond technical and financial hurdles, there is the human element. MOSA’s principles contrast starkly with traditional acquisition and integration practices, meaning program managers and system integrators must adopt an entirely new mindset: one that prioritizes modularity, flexibility, and iterative upgrades over individual acquisitions. Training requirements and maintenance protocols must evolve in parallel to complement modular systems.

Overcoming these challenges requires deliberate planning, extensive coordination, and technical precision. It’s important for system designers to integrate modularity into all designs from the outset, at both the interface and application layers. Open, standardized interfaces enable interoperability and reduce integration friction, while application layer flexibility ensures modular components can serve multiple functions based on operational requirements.

System architectures should also support future growth by allowing for rapid upgrades. When implemented effectively, these strategies allow modular systems to adopt plug-and-play upgrades, replacing outdated components without disrupting the broader platform.

MOSA in action

A concrete example of MOSA in action is the SAVS 360, an AI-powered situational-awareness video system for armored vehicles. SAVS 360 integrates day and night sensors with advanced video processing to give crews 360-degree visibility and real-time threat detection, even while the vehicle’s hatches are closed.

This system exemplifies MOSA principles through its modular architecture, enabling upgrade or replacement of sensors, processing units, and interfaces without impacting the entire vehicle. Open system integration ensures that SAVS 360 can be deployed across multiple platforms, supporting interoperability and rapid technology refreshes.

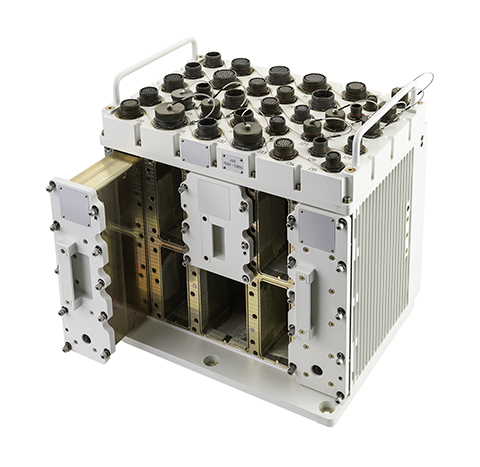

The system’s core technology is an advanced AI-powered video matrix. Its modular nature enables any configuration of sensors to be easily integrated into a central processing unit distributing real-time data and video analytics throughout the vehicle’s systems and users. (Figure 2.)

[Figure 2 ǀ The SAVS 360 is a 360-degree, live-view situational-awareness system built for armored vehicles operating in dynamic and high-risk environments. The system leverages artificial intelligence (AI)-driven processing capabilities with a mission computer, high-end video matrix, and a wide array of sensors. Image courtesy IMCO.]

Take two: Using the module

An ever-growing challenge is the need to be able to adopt improvements in hardware and software for the different vehicles’ applications.

IMCO’s vehicle computing module enables a “remove and replace” approach to the main computing modules of the most advanced armored-vehicle platforms. A unified box hosting upgradable, standalone, computing units enables both logistics and support flexibility as well as ease of upgrade in both software and hardware capabilities without the need to change anything in the vehicle. (Figure 3.)

[Figure 3 ǀ Shown: The SAVS 360 vehicle computing module.]

The remove and replace approach demonstrates how modular, open systems can accelerate fielding, simplify maintenance, and rapidly integrate emerging technologies.

After the shift

MOSA is a fundamental shift in the DoD’s acquisition philosophy. By emphasizing modular design, open interfaces, and life cycle-oriented planning, MOSA will enable the DoD to deploy adaptable, competitive, and cost-effective systems.

Despite challenges such as cybersecurity concerns, the reality of legacy system upgrades, and resource constraints, MOSA is an imperative goal. With consistent and clear coordination between the DoD and its industry partners, intentional design practices, and well-defined standards, the defense industrial base can overcome these obstacles to attain MOSA.

With technological advancements outpacing acquisition timelines, MOSA is a powerful and necessary strategy for the DoD to maintain its superiority on the world stage. It’s vital for the defense industrial base to wholeheartedly embrace this new mindset and support the DoD as it transitions to MOSA at scale.

Marc Steiner is the CEO of IMCO America. In this role, he ensures IMCO America delivers cutting-edge technologies that advance aerospace and defense missions. Before joining the private sector, Marc served as a U.S. Navy officer and Fleet Support Branch Chief at the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

IMCO America • https://imco-america.com/