Connected combat: How U.S. military branches are learning to fight as one

StoryOctober 09, 2025

An Army radar detects incoming missiles while a Navy ship simultaneously tracks the same threats and an Air Force interceptor calculates engagement solutions. Within seconds, all three systems share data, coordinate responses, and execute a unified defense strategy without human operators manually relaying information between branches. This level of integration represents the end goal of Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2); achieving this level of connection requires fundamentally rethinking how military systems communicate in hostile environments.

It’s all in the timing: Today’s adversaries can detect threats, make decisions, and launch attacks faster than traditional command structures can respond. When an Army radar spots incoming missiles, precious minutes tick by as operators relay information through radio calls and secure channels to Navy ships and Air Force interceptors that could help defend against the attack.

The solution sounds straightforward – connect everything electronically so all military branches see the same threats simultaneously. For the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) that is the Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2) strategy, which will aim to connect sensors and shooters across all military services into a single network, ultimately enabling Joint All-Domain Operations (JADO) in cooperation with the U.S.’s allies, according to Lockheed Martin.

However, creating those connections opens new vulnerabilities that adversaries can exploit. Cloud networks that enable lightning-fast data sharing also create targets for cyberattacks. Communication links that work perfectly during training exercises may fail completely when enemies jam radio frequencies or cut internet cables.

Defense contractors are racing to close the breach with technologies borrowed from commercial Internet companies that are hardened for military use. Using these tools, artificial intelligence (AI) systems process sensor data faster than human analysts can read it, backup satellite networks activate automatically when ground communications fail, and zero-trust security protocols assume every network connection might be compromised and plan accordingly.

The role of CJADC2

The CJADC2 concept addresses a basic inefficiency: Military branches have traditionally fought with limited awareness of what other branches were doing, which leads to missed opportunities and wasted resources.

“The ‘C’ actually stands for combined,” says Ron Fehlen, national security space mission architect vice president at Lockheed Martin (Littleton, Colorado), during his keynote address at the CJADC2 At the Edge 2025 Virtual Summit presented by Military Embedded Systems. “It focuses now on exportability and how we share this across multiple systems, and not just the systems, but also our allies.”

[To watch the archived event, visit https://resources.embeddedcomputing.com/series/cjadc2-at-the-edge-2025-virt/landing_page .]

Instead of Army radar operators spending minutes relaying threat information through human channels, all systems would share data instantly.

“In practical terms, it means a Navy ship, an Army radar, and an Air Force interceptor can all see the same picture and respond as one,” says John Breitenbach, director of aerospace and defense markets at RTI (Sunnyvale, California).

The vision extends internationally, which adds complexity since systems must work not only across U.S. branches but also with allied systems using different technologies and security protocols.

Justin Pearson, senior director of architecture and business growth for aerospace and defense at Wind River (Alameda, California), describes CJADC2 as “focused around the concept of enabling faster, more informed decision-making across all branches of the military” by connecting “systems/sensors/devices and decision-makers across air, land, sea, space, and cyber domains in real time.”

The security challenge

Connecting military systems to cloud networks creates a problematic situation, however: The same links that speed up decision-making also give adversaries more ways to infiltrate. Traditional military radios were built to work alone, but CJADC2 requires sharing classified information across networks that hostile forces actively target.

“The minute you spread data across more networks or push it to the cloud, you expand the attack surface,” Breitenbach notes. “Cloud connections, in particular, are prime targets for adversaries.”

Military systems cannot simply rely on the stable internet connections that commercial cloud services take for granted. “Tactical systems operate at the edge, where connectivity may often be intermittent and adversaries are actively trying to disrupt communications,” Pearson says. The challenge involves “maintaining cybersecurity and data integrity in highly dynamic, often hostile environments,” he adds.

Military planners must prepare for the worst case from Day 1, Breitenbach says. “The starting assumption has to be that edge systems will often be operating in DDIL environments – disconnected, degraded, or contested,” he says, adding that systems can’t just shut down when cloud connections fail.

“Those systems need to continue functioning independently, and when they do reconnect, the data has to move securely,” Breitenbach continues. “That requires authenticating endpoints, encrypting data, and protecting information in flight.”

The requirements go beyond typical cybersecurity. Military systems must provide “secure data transmission, authenticating users and devices, and protecting against cyber intrusions, all while maintaining low latency,” Pearson notes. This must-have combination of security and speed creates engineering problems that commercial systems never face.

The solution requires “strong encryption, zero-trust architectures, and resilient network designs,” Pearson says. Technologies that assume networks are already compromised and plan accordingly, he adds.

Leveraging commercial innovation

The technologies addressing these challenges borrow from commercial innovations but harden them for life-or-death situations. “I see a lot of technologies like zero-trust networks, for example, where it’s recognized that you may not be able to trust the network you’re on, but you still need to pass the data,” Fehlen says.

The stakes differ dramatically between civilian and military applications. Fehlen illustrates with a personal example: “I’m flying out here to D.C. last night, and I’m on the plane and I’m doing email and I’m chatting with folks, and all of a sudden, the WiFi on the plane goes out. For me, it’s an inconvenience. In wartime or an operational environment, that’s a big deal.”

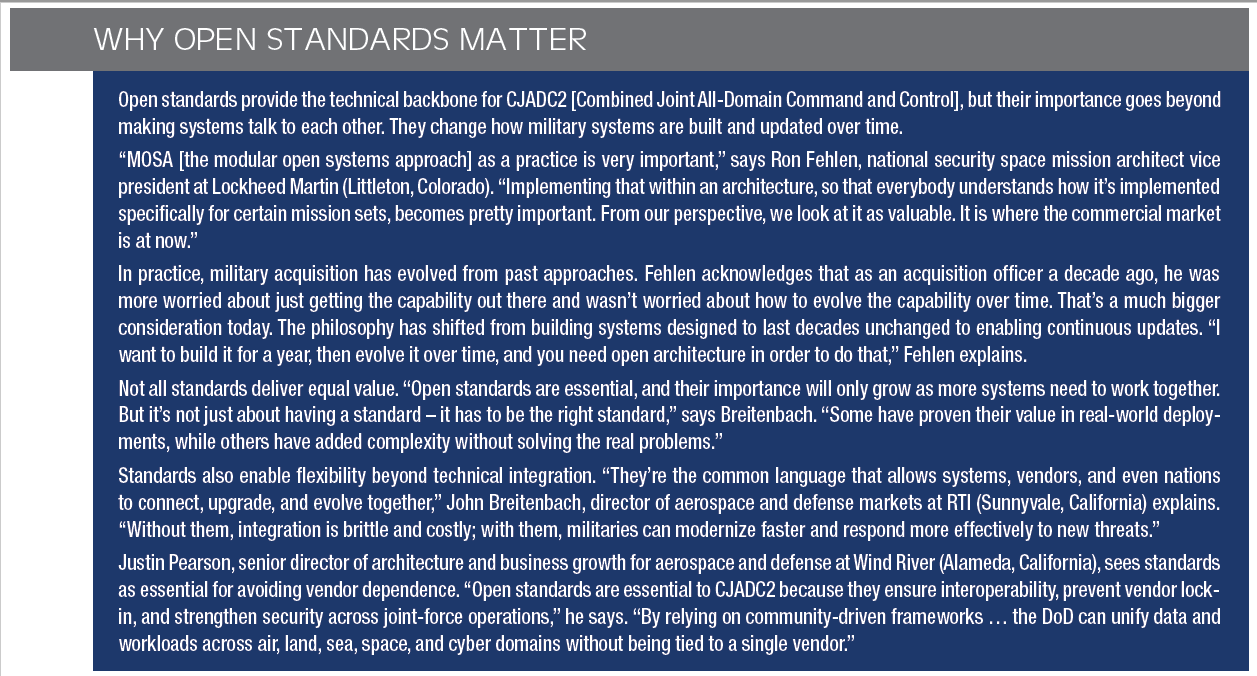

Defense contractors must design for inevitable disruption rather than hoping communications won’t fail. “The key is designing for resilience,” Breitenbach says. “In a contested environment, you have to assume communications will be interrupted – the question is how systems continue to operate when that happens.” (Figure 1.)

[Figure 1 | The Independence-variant littoral combat ship USS Savannah (LCS 28) transits under the Coronado Bridge as it returns to Naval Base San Diego. RTI connects disparate systems, merges multiple languages on multiple operating systems, and handles communications links and legacy interfaces for the LCS. U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Josh Coté.]

“The answer is redundancy and smart data handling,” he continues. “ By sending information over multiple paths, buffering it when links go down, and backfilling once they come back up, systems can maintain continuity.”

The approach accepts that stopping all attacks may be impossible. “You can’t stop an adversary from trying to jam or disrupt communications, but you can make sure the mission continues despite it,” Breitenbach notes.

Pearson points to emerging solutions: “Technologies such as mesh networking, low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellations, and software-defined radio (SDR) are showing some promise. These systems can dynamically reroute communications, operate across multiple frequencies, and adapt to jamming attempts.”

AI’s potential

CJADC2’s success creates an unexpected problem: Connecting military systems means commanders will drown in more information than humans can process. Without AI to sort through this flood of data, the connectivity designed to speed decisions could slow them down by overwhelming operators.

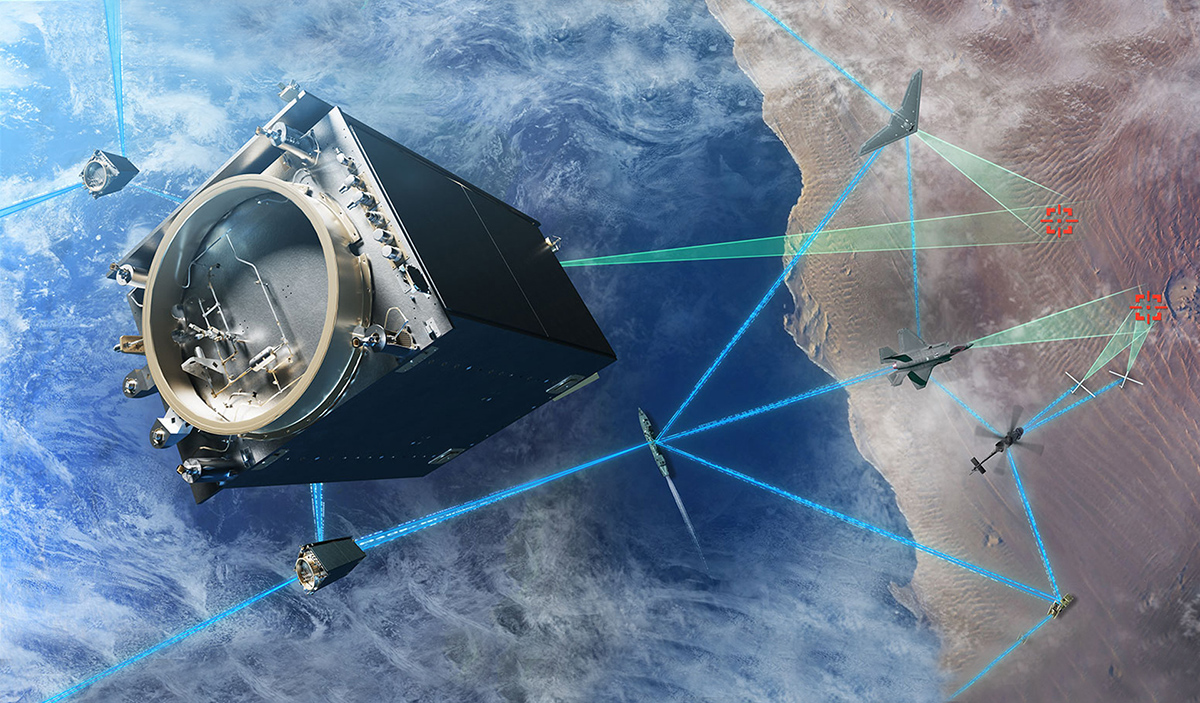

“Once you get all that, you’re going to have a lot more than you had before,” Fehlen says. “How do you make sure that it doesn’t become a room full of humans that has to go through it in detail?” The solution is for AI to step in and “put context to what they’re translating, so that they can turn that into something actionable,” he says. (Figure 2.)

[Figure 2 | Lockheed Martin’s CJADC2 Interoperability Factory uses a modular, open-architecture software stack to connect legacy and next-generation systems, including AEGIS, F-35, HIMARS, and SDA satellites. Image courtesy of Lockheed Martin.]

The relationship works both ways. While AI processes more information, it needs reliable data to function, Breitenbach says. “AI is only as good as the data it receives,” he says. “I like to say data is oxygen for AI – without it, the algorithms suffocate.”

This dependency becomes critical when AI systems make life-or-death classifications.

“Think about a counter-UAS [uncrewed aerial system] scenario – an AI algorithm may be tasked with classifying whether an object is a bird, a drone, or a missile,” Breitenbach explains. “To make that call, it needs radar data, video feeds, and threat libraries, all fused together in real time.”

Timing leaves no room for error. “If that data is delayed, incomplete, or compromised, the AI can’t perform its mission – and the system could fail at the moment it’s needed most,” he adds.

Pearson sees AI handling multiple functions: He believes it could help with filtering noise, detecting anomalies, and prioritizing threats in real time. “This allows commanders to focus on strategy while machines handle data fusion, pattern recognition, and rapid-response recommendations,” he says.

Systems architects will need to take location into account as they build these AI systems: “It will be important to have AI applied as close to the sensors and other sources of data as possible for a host of reasons: latency, security, network bandwidth, and robustness in a DDIL environment,” Pearson notes.

An unclear timeline

Predicting when the military will achieve complete cross-branch integration proves as challenging as the technical hurdles themselves. Industry experts agree the transition will happen gradually rather than through a single dramatic rollout.

“We’ll probably wake up one day and realize it,” Fehlen says. “And the reason I say that is because the ‘it’ starts from a very, very simple approach.” He draws an analogy to consumer technology: “If I think back to the first versions of the phone that I hold in my hand … I finally got rid of my last flip phone on my Verizon account as of two years ago, because they would no longer support it.”

Breitenbach sees substantial progress in specific areas. “Programs like IBCS [Integrated Battle Command System] and CBC2 [Cloud Based Command and Control] are showing what joint command and control can look like,” he says.

The challenge now involves connecting existing capabilities. “The next big step – and it’s what Golden Dome is all about – is pulling these together so they operate as one unified system of systems,” Breitenbach explains. [Golden Dome is a multi-layered missile defense system being developed by the U.S. military.]

Pearson also believes that while progress is accelerating, full integration is “still a multiyear journey,” with the main challenges being cultural alignment, technical interoperability, and a general harmonization across services. “Pilot programs and joint exercises are demonstrating the potential, but scaling these capabilities globally and securely will require sustained investment, collaboration, and innovation,” he asserts.