Semiconductor supply-chain challenges

StorySeptember 13, 2021

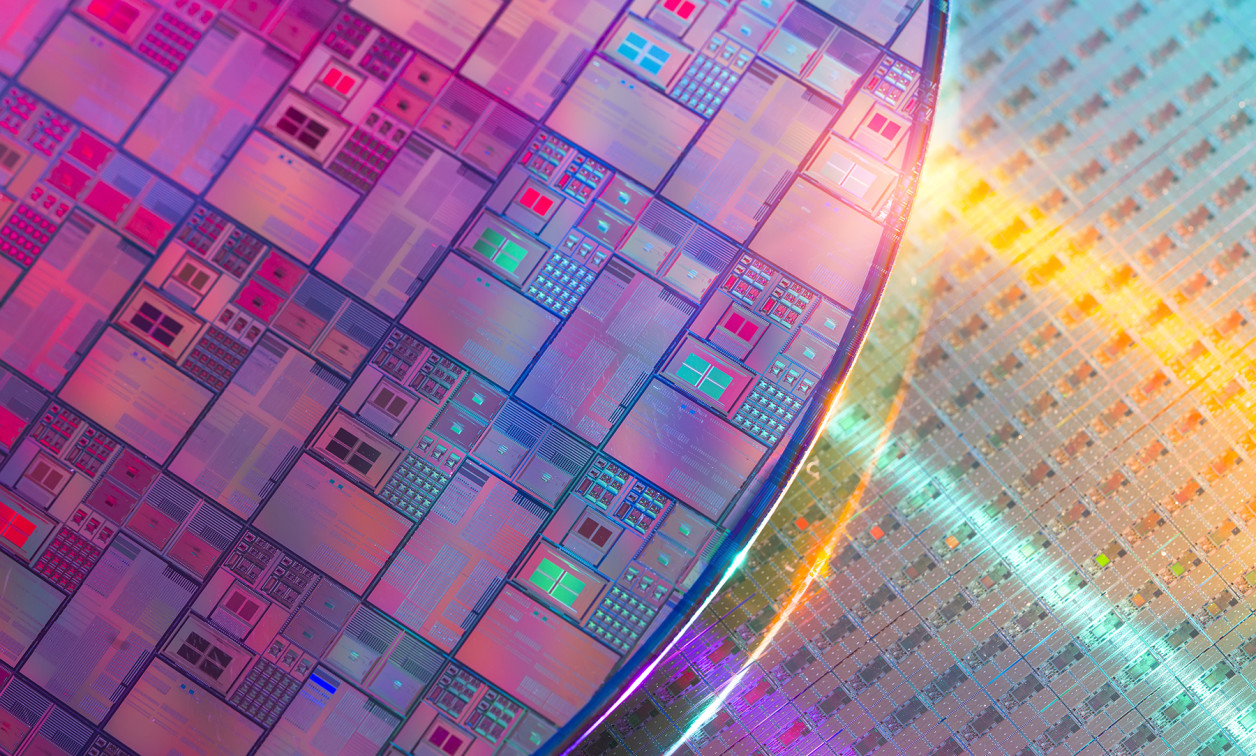

Military suppliers, being essential businesses, weathered the pandemic and economic shutdowns admirably thanks to strong defense funding. Yet even this stalwart industry is feeling the ill effects of the global chip shortage and the consequences of its reliance on offshore semiconductor manufacturing. The U.S. government is committed to returning chip production to the States, but whether that move will be enough and in time to save the industry is yet to be determined.

Much of the world’s supply of semiconductors for use in high-performance computer systems are made outside the U.S., in Asia, specifically in Taiwan. When COVID-19 spread, the world saw industrial and automotive plants shut down and the fabs that provide the semiconductors and for electronic systems also reduced inventory, fearing reduced demand with folks no longer going to work and huddling indoors in quarantine.

“With the new tech shortages, military electronics suppliers face a perfect storm of multipole factors negatively impacting the supply chain,” says Frank Cavallaro, CEO of A2 Global (St. Petersburg, Florida). Cavallaro points out three main causes:

- “There has been consolidation at the brand level and at the back end/raw material level with silicon fabrication facilities overseas. Visibility and control have gone away and they find it has becomes a pecking order, and they are not at the top of that list.

- A second cause is the pandemic: Semiconductor manufacturers underestimated the demand for PC chips due to a surge of work-from-home employees and other reasons.

- Restarting the fabs: When the fabs closed due to COVID issues, it wasn’t like flipping a light switch to turn it back on. Generally, it’s an 18- to 25-week lead time before the first product is ready to go. Depending on manufacturer prowess, that gap could be even longer; that’s also before you factor in demand or geopolitical concerns. “Any time there is a hiccup, you have to start from zero again to get to the qualification process. It takes time to bring this capacity online and they will not be building today’s technology, but the next generation technology, the next geometry reduction.”

Closures were not even economically forced, but done to protect against spread of infection. “During the pandemic, many auto plants closed to reduce COVID infections among their employees,” says Ray Alderman, chairman of the board of VITA, in his “State of the VITA Technology Industry Report Spring 2021 Edition.” “The carmakers called up the computer chip factories and delayed shipments of their orders. Production started up in mid-2020, but a shortage of semiconductor chips shuttered those factories yet again in early 2021.”

In short: They stopped making computer chips, then everybody started staying home and wanted new computers and gaming consoles to keep them company.

“With everyone staying home and working from home, the demand for new cellphones, new TVs, computers, and game boxes soared,” he continues. “The semiconductor industry shifted their fabs over to make more complex and more profitable chips for those markets. When the carmakers called up the chip companies and requested their parts, there was no production capacity left to make them.”

The result was lead time that went from two to four weeks to almost a year for some components. Military computer suppliers found it quite frustrating.

This current atmosphere is unique, says Jason Wade, president of ZMicro (San Diego, California). “For some electronic components we are seeing 52-week lead times. Tesla builds factories in less time.”

Not only components have disappeared, but component suppliers have also gone out of business. “Some manufacturers disappeared off the map in the last couple years,” says Michael McCormack, president and CEO of CPU Tech (Prescott, Arizona). “Capacitors, resistors, and other components have disappeared out of Taiwan and China. Everything got decimated, pushing lead times out and increasing pricing.”

While some of these supply-chain problems existed pre-COVID, the pandemic made them worse. “When the pandemic hit everything changed, so the material supply challenge is just a symptom of that bigger picture,” says Steve Motter, vice president, business development, IEE (Van Nuys, California). “It’s really impacted manufacturing channels, as they don’t have the inventory at the OEM level as in years past. In many cases these inventories have gone from 100% to zero. We are seeing where distributors are going back to factory lead times. That’s an outcome of the push to have less inventory at the OEMs and at the distributors.”

Defense industry impact

The military-industrial complex still exists, but it does not have the power to drive the roadmaps and tech investment of semiconductor manufacturing. So that sector is at the mercy of the market just like the rest of the consumer world.

“Historically, the military drove technology innovation in their platforms, which live for decades,” Cavallaro says. “They could drive the roadmaps and lead times of semiconductor manufacturers. Since the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) transitioned to a COTS [commercial off-the-shelf] procurement model in the 1990s, that became less and less the case. Today, the military is more a consumer of technology than a driver and is at the whims of commercial supply chains, especially when it comes to semiconductors.

“The military doesn’t don’t have the capability to fund wafer starts and tech spends and will continue to chase end of life (EOL),” he continues. “Semiconductor life cycles today are measured in 90-day cycles, not years or decades.”

Military electronics suppliers from printed circuit board (PCB) makers to rugged-computing designers to the primes and system integrators are having to pivot from traditional procurement practices and get creative.

“They have caused a refocus on resources to either redesign products or go to the open market to find them,” says Maria Gillespie, Director of Product Marketing – Die for Micross (Orlando, Florida). “This of course has a ripple effect and raises a need for other services such as counterfeit risk mitigation and/or component harvesting. In some cases, this shift is delaying production while also depleting any reserve inventory. There continue to be severe supply and demand gaps for industries left out of foundry prioritization. I expect to see an increase in cited DO ratings, and likely more pressure to ensure they are being added and included.”

Dealing with the current shortages is a different animal than managing EOL situations. “Managing new product or current product supply chains is whole new paradigm,” Cavallaro says. “The military integrators and the DoD are not used to managing their semiconductor supply chain without considerable time and energy spent on it. They are often two or three levels removed from semiconductor purchasing and are more focused on EOL and long tail challenges, which deal with managing shortages of older tech.”

COTS suppliers and roadmaps

COTS suppliers are used to dealing with product shortages for components that go EOL and often must deal with managing the short life cycles of commercial components, but that may not necessarily help them with the semiconductor shortage.

“[They] are better suited for typical EOL, long-tail tech sourcing,” Cavallaro says. “The challenge today is that the shortages are not just with EOL products but with current technology. Before the current shortages, they were managing a handful of parts in long tail, but now it’s a mix of long tail and current tech and none are getting attention from the supply chain.”

Developing roadmaps is now even more challenging. “I think the visibility is always difficult when you go past 180 or 360 days,” Cavallaro says. “These folks manage long tail supply issues, but now they are having to focus on supply-chain interruption, which means long tail gets neglected even more. This is becoming an increasing problem for them, for managing DMSMS [diminishing manufacturing sources and material shortages] challenges. There isn’t just one solution, either. It will take a cocktail of supply-chain strategies to stay ahead. “You can’t put your finger in the dike and expect to stop the flood; a leak will spring somewhere else,” Cavallaro says. “The problem can’t be solved with one type of methodology.”

“There are so many potential bottlenecks – wafers being built at one mega plant, technology being developed at another plant, packaging and test being done somewhere else,” he continues. “You can’t point a single finger. In some cases, maybe the most economical solution is not the most efficient.”

Managing the inventory for the most critical programs takes constant planning, often at least a year ahead.

“Thanks to tariffs and other delays, even our strongest suppliers have gone from eight weeks to 30 weeks for their delivery timetables,” says Marti McCurdy, owner and CEO of Spirit Electronics (Phoenix, Arizona). “We are trying not to play into any of that. We work to make sure the most critical programs do not get shortchanged on supply by planning 12 months ahead for such situations. Our supplier-managed inventory program is helping secure the supply chain with projected forecasting and placing orders to secure a solid backlog with our suppliers even though the lead time is long.”

Defense electronics suppliers must ensure that they continue to strategize for the long term even with these short-term challenges, and that they’re not just reacting to each crisis.

“Although we have in many cases entered a reactive time, the need to understand future demand (forecasting) continues to be key,” Micross’ Gillespie says. “If we are to get out of this at some point we do need to start looking further ahead and asking that of customers. Utilizing a company like Micross to step in at the die and wafer level and provide packaging, testing, or product continuation solutions to mitigate some of these issues right now can be a potential path forward for suppliers.”

Yet, many of the COTS suppliers feel their experience gives them an advantage that others don’t have. “As a supplier of military systems that leverage commercial components, we are used to managing the supply chain and obsolescence challenges that come with commercial technology,” ZMicro’s Wade says. “That leaves us better prepared than others.”

Geopolitical concerns

Geopolitical concerns around semiconductor manufacturing have U.S. government leaders concerned as much as those issues related to the pandemic. Many feel the U.S. is too dependent on semiconductor foundries located offshore in Taiwan.

While the U.S. is friendly with Taiwan, China still considers Taiwan part of China and they want it back. A potential war over Taiwan’s independence leaves U.S. officials quite concerned.

“Taiwanese contract manufacturers account for two-thirds of global chip sales,” according to an article in the May 1-7 issue of the Economist titled “Living on the Edge.” The largest of these is Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), which has pledged to open a foundry in Arizona in 2024. Even with that expansion, though, the company still maintains most of its expertise in its home location, with about “90% of its 56,800 staff … based in Taiwan,” according to the Economist article.

“Many Taiwanese IC suppliers depend on China for their components,” McCormick says. “China has placed tremendous geopolitical pressure on these suppliers, so that if they don’t respond right away to a request their supply chain is cut off. We made a decision to eliminate our dependency on China and Taiwan [and] moved our supply chain to more U.S. suppliers.”

It’s not just the manufacturing but also the expertise and quality of product these Taiwanese fabs produce that will have to be duplicated on U.S. shores.

“TSMC and Samsung are the only two semiconductor companies to push transistor geometries down to the 7 nm level, and both are moving toward 5 nm processes now. Intel has tried and failed to get past 10 nm for years,” Alderman says. “All the advanced processor chips today are being made by TSMC and Samsung, which presents a potential supply chain problem for many segments of the U.S. economy if something goes wrong.”

The Wall Street Journal also reported that TSMC also “plans to increase the prices of its most advanced chips by roughly 10%, while less advanced chips used by customers like auto makers will cost about 20% more,” in article titled “World’s Largest Chip Maker to Raise Prices, Threatening Costlier Electronics.”

These mounting economic and domestic pressures are pushing the U.S. government to return the capability to the U.S., but expensive challenges remain. “Domestic production is very focused on lower-cost ways to respond to military needs,” says Dave Young, CTO for Cobham Advanced Electronic Solutions (CAES – Arlington, Virginia). Bringing semiconductor manufacturing onshore “means competitiveness from a cost standpoint will be challenging,” he continues. “But it needed a kick-start, as we are seeing lead times taking as long 18 months and need all avenues for our disposal to meet demands.” CAES, which historically has been foundry-agnostic, now partners with the SkyWater Technology foundry in Bloomington, Minnesota, for U.S.-based strategic rad-hard manufacturing, Young adds.

The DoD is increasing funding for domestic microelectronics production and investment is necessary for onshore IC production to succeed. “For, example the Air Force’s FY 2022 budget request calls for $885 million for commercial microelectronics,” says Larry Hayden, senior director, sales and business development, Vorago Technologies (Austin, Texas).

“This isn’t the first time there has been a push to increase U.S. semiconductor manufacturing,” he says. “In the past these have been seen as fads, but what is unique this time is the significant investment from a variety of sources – from the U.S. government to Intel to global foundries – into U.S. facilities.”

Part of the DoD’s plans revolve around the Rapid Assured Microelectronics Prototypes – Commercial (RAMP-C) program. The program was created to facilitate the use of a commercially viable onshore foundry ecosystem that will ensure DoD access to leading-edge technology, while enabling the defense industrial base to leverage the benefits of high-volume semiconductor manufacturing and design infrastructure of commercial partners like Intel, according to an Intel release. For more on RAMP-C and Intel’s plans for chip manufacturing in the U.S., see sidebar on Page 46.

The domestic winner for expanded semiconductor production appears to be the Phoenix area. “TSMC has announced plans to build a new fab in Phoenix. In late March, Intel [also] announced two new fabs for the Phoenix area,” he continues. “Phoenix is becoming a southwest version of Silicon Valley. Samsung was planning to build a new fab in Austin, Texas, but the winter storm that cut power to that region for days in February 2021 has inspired them to look at other locations like Phoenix.”

Cavallaro says he thinks the DoD’s plans will go through “as our awareness and acuteness of the problem is strong. It also has a broad base of support from the political side. Whether it will be enough is the billion-dollar question. If one does the math on wafer starts, roadmaps, and the sheer number of wafers needed to meet demand, there is a fear we will come up acutely short.

“Yet, with the demand profile as dynamic as it is, it’s tough to tell how things will be so far in the future,” he continues.