Liquid cooling unlocks performance in embedded systems

StoryJuly 31, 2025

Over the past several years, CPU outputs have more than doubled in the continuous drive for enhanced processing performance and speed from military embedded computer systems. While these increased power densities create more heat that needs to be managed effectively, the industry is in fact nearing the limits of air-cooling effectiveness. Liquid cooling is the next step to optimize thermal management of embedded computer systems and reduce throttling.

Today’s CPUs and GPUs are delivering more performance than ever. As power densities climb and thermal loads surge, traditional air-cooling methods are beginning to show their limits. For engineers developing mission-critical systems, managing heat is central to unlocking the full capabilities of advanced computing hardware. The industry is approaching a critical inflection point where innovation in heat management will define the next generation of embedded system performance.

Thermal stress introduces a critical throttling threshold beyond which system performance begins to deteriorate. While definitions of this threshold may vary across manufacturers, in defense-grade computing environments, any measurable decline in computational throughput – however minimal – is operationally consequential. Within mission-critical contexts, any degradation of CPU or GPU efficiency can compromise system responsiveness.

Validating system performance under maximum operational stress is essential to ensuring reliability in mission-critical scenarios. Stress-testing systems to 100% CPU utilization provides critical insights into thermal tolerance, processing stability, and overall system resilience; this type of testing is critical for ensuring performance under peak load conditions.

Air cooling approaching effective limits

The performance of military embedded computer systems depends on adequate cooling, but the industry is reaching the limits of air-cooling effectiveness. Liquid cooling increases the reliability of the overall system, lowering the temperature and reducing throttling; the technology also enables a reduced overall footprint with a tradeoff of increased weight.

There are inherent challenges when moving from air-cooled to liquid-cooled designs. For one, when there are requirements for removable components, liquid cooling becomes challenging. One solution is conduction-cooled modular designs, such as single or multidrive packs, which enables the isolation of components that need to be repeatedly removed and installed, while still tying them into the sealed, liquid-cooled solution.

Legacy air-cooled applications can also prove challenging when converting to a liquid-cooled solution. The standard 19-inch rackmount infrastructure commonly used across U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) applications, especially within aircraft and surface vessels, are typically designed to support air-cooled solutions. Pivoting to a liquid-cooled solution will often require customer investment in infrastructure to support the heat-rejection needs of liquid-cooled designs. Heat-rejection infrastructure typically includes addition of pump, flow meter, and radiator to expel heat.

Design considerations for liquid cooling

Effective liquid-cooling design must account for leak mitigation to protect critical electronic components. This hurdle may be addressed by positioning liquid plenums exterior to the systems, ensuring in the event of a leak that any escaped fluid is exterior to the enclosure. This architecture effectively isolates fluid pathways from sensitive circuitry, thereby eliminating the risk of fluid ingress and associated component failure.

Trying to quantify the performance difference between air-cooled and liquid-cooled systems is difficult because there are numerous variables that impact performance, including ambient temperature, fluid temperature, fluid pressure, flow rate, and more. However, once CPUs start passing the 500-watt threshold and are subject to an elevated ambient temperature, a platform that supports integration of a liquid-cooled solution will likely be needed.

Software innovation continues to outpace the processing capabilities of modern CPUs and GPUs, creating a persistent performance gap. As software teams push for ever-greater computational power, the demand for increased processing throughput and energy consumption shows no sign of slowing. Customers are now routinely specifying systems with four to six embedded GPUs – compared to just one or two in prior generations. Each additional GPU contributes incremental wattage; cumulatively, this increase presents difficult thermal-management challenges. In many cases, traditional air-cooling solutions are no longer sufficient to maintain optimal operating temperatures. With the increase in processing power and SWaP limitations in the future, there is going to be a transition point where a majority of the systems become liquid-cooled. This shift will be necessary to take advantage of ever-advancing data-center technology.

An integrated approach for optimal thermal management

To fully optimize high-performance computer systems, engineers must take an integrated approach to cooling. As increasingly higher-power systems come online, liquid cooling will be by far the most effective medium to dissipate heat. While some solutions actually are 1100% liquid-cooled, there are situations where it is neither feasible nor practical to liquid-cool every single chip at risk of throttling. In these situations, engineers find themselves optimizing for not only maximum thermal performance, but also weight and cost. This space is where hybrid liquid- and air-cooled systems should be considered.

For hybrid systems, the optimal thermal-management approach is that of a targeted thermal-zoned enclosure, for which the engineers perform detailed thermal analysis evaluating each chip at risk for throttling. They identify how much power and heat each component in the environment generates. A decision can then be made whether the components should be air- or liquid-cooled, which leads to building of zoned systems that control all air and liquid fluid movement throughout the enclosure. Custom ductwork and heatsinks can be designed to optimize airflow and utilize direct-to-chip (DTC) liquid-cooling flow paths.

While liquid cooling is not a new technology, liquid-cooled designs for the rugged embedded military space have unique requirements compared to data centers. Commercial cloud data centers have seven or eight major suppliers that have created liquid-cooling solutions based off reference designs for rackmount systems. While these solutions work for rackmount, they cannot be used in an embedded military space. Data center liquid-cooling solutions aren’t designed for movement, vibration, shock, and other military-standard specifications. Using non-mil-spec parts introduces the risk of leaks and compounded maintenance complications.

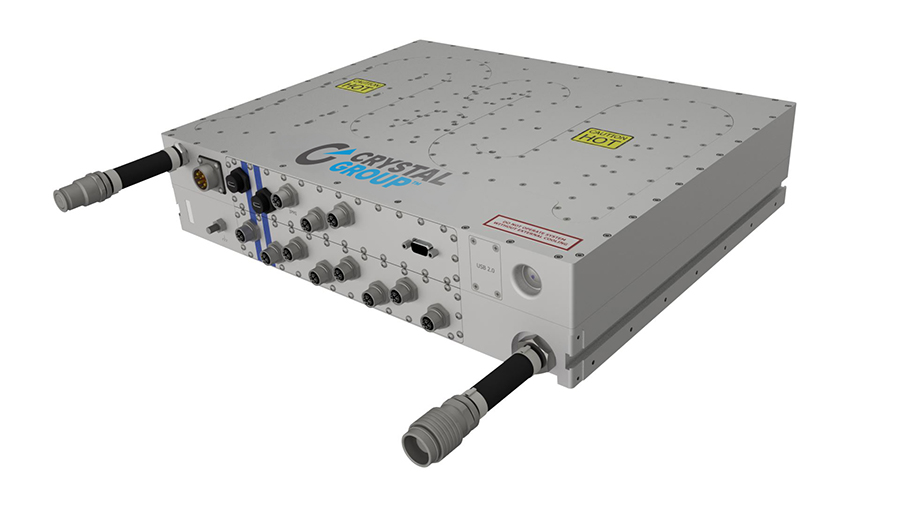

Mitigating the risk of fluid leakage in embedded systems requires a purpose-built cooling architecture – one that is physically isolated and ruggedized to operate independently from sensitive electronics. Beyond leakage prevention, key engineering challenges include managing coolant pressure drop and optimizing fluid dynamics. The solution is custom-designed flow paths and variable-area plenums, which modulate flow rate and pressure as coolant removes heat from critical components. (Figure 1.) This level of control ensures precise thermal management and maximized heat transfer efficiency throughout the system.

[Figure 1 ǀ The AVC0500 rugged sealed server is intended for compact AI-enabled performance with advanced liquid cooling in the most extreme environments.]

Zoned cooling and beyond

Rising power densities are inevitably pushing military embedded computing toward zoned cooling solutions. The industry is already seeing the limits of traditional forced air-cooling methods, particularly in environments with high ambient temperatures where thermal headroom is scarce. Liquid cooling extends operational temperature margins, maintains system reliability, and offers acoustic benefits. This all comes while keeping component heat loads below throttling thresholds so full performance potential can be realized. For the next generation of high-performance, mission-critical systems, liquid cooling is no longer optional – it’s essential.

Morgan Uridil, as Manager, Advanced Program Pursuits at Crystal Group, leads a team of engineers working on expanding the limits of rapid prototyping and high-stakes compute solutions. She has a background in R&D and product development and earned a bachelor of science degree in manufacturing and design engineering from Northwestern University.

Crystal Group https://www.crystalrugged.com/