Onshoring legacy semiconductors: Addressing the supply chain

StorySeptember 04, 2025

The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) relies on legacy semiconductor components to maintain critical defense systems, including radar, missile guidance, and communication equipment. However, many of these low-value parts, originally designed decades ago, are no longer produced domestically, with manufacturing shifted to foreign suppliers. This dependency introduces risks, including supply-chain disruptions and intellectual property vulnerabilities. Addressing these shortfalls requires collaboration with the DoD to reverse-engineer these components, recover technical data, and establish an entirely domestic supply chain. Technical processes and innovations – including data-recovery methodologies and the application of multi-electron beam direct write (MEBDW) lithography – can have positive implications for U.S. military embedded electronics.

Legacy semiconductors, often based on older process nodes (e.g., 180 nm or larger), are critical for maintaining defense systems but lack commercial viability for high-volume production.

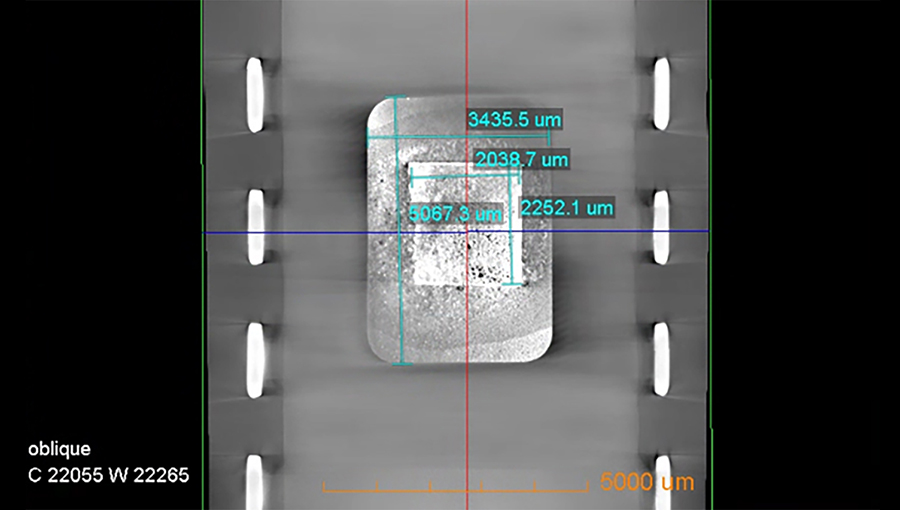

Over the past few decades, U.S. manufacturing capabilities for these parts have diminished as companies prioritized advanced nodes (e.g., 7 nm or 5 nm) targeting advanced systems or consumer electronics. As a result, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) faces challenges in sourcing reliable and secure components domestically, as many parts are now only produced overseas. (Figure 1.)

[Figure 1 ǀ U.S. manufacturing capabilities for larger semiconductors have waned over the past few decades as companies prioritized smaller advanced nodes (5 nm and 7 nm, for example) aimed at use in advanced systems and consumer electronics.]

The absence of domestic foundries for these components creates vulnerabilities. Supply-chain disruptions, such as those seen during recent global chip shortages, can delay maintenance or upgrades for defense systems. Additionally, foreign manufacturing raises concerns about intellectual property security and potential tampering. Original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) often express a willingness to support DoD requirements; however, they too lack the necessary infrastructure to produce these legacy systems, as their focus has shifted to newer technologies.

Technical data for older components is another hurdle. Schematics, process recipes, and other documentation are often incomplete, outdated, or scattered across old contracts. Without this data, reproducing parts to exact specifications is nearly impossible, prompting the need for systematic reverse engineering and data recovery.

Recovering technical data for legacy parts

One of the major barriers to onshoring legacy semiconductor production is the lack of accessible technical data. Many legacy parts were designed decades ago and lack comprehensive documentation due to discontinued production lines or misplaced records. Moreover, the OEMs themselves often no longer possess the manufacturing capability or detailed data packages. These facts drive the need to reverse-engineer parts to access the technical data. This is a manual, time-intensive process that depends on personnel availability, system access, the ability to trace contract numbers, and time involved in reviewing contract data requirements lists (CDRLs).

Drawing on digital forensics, a repeatable process was developed to recover technical data for legacy semiconductors. This process involves:

- Contract tracing: Using DoD contract databases to locate original contracts and associated CDRLs, which specify deliverables like design schematics, material specifications, and manufacturing processes. Although this may seem straightforward, layers of bureaucracy can significantly delay or deny access – often, the effort is dependent on personality rather than legality.

- Data extraction and validation: Employing forensic techniques to extract and validate data from archival formats, including legacy file systems and obsolete storage media.

- Documentation reconstruction: Reconstructing incomplete data sets by cross-referencing existing DoD systems (e.g., standard parts) and OEM records, ensuring compliance with security standards.

This approach enables data recovery and establishes a standardized methodology for future recovery efforts. Refining this process will enable a transition from a manual to an automated one, utilizing artificial intelligence (AI) tools that leverage machine learning to parse and organize data, thereby further reducing recovery time.

The importance of TDPs and data rights

Retrieving technical data packages (TDPs) from more than decade-old federal contracts presents unique challenges due to the retention policies outlined in 44 USC Chapter 31, related Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR) requirements, and practical issues with legacy data management. However, TDPs typically contain detailed technical specifications, drawings, and documentation for items such as semiconductor manufacturing equipment or defense systems and are essential for reverse engineering, maintenance, or reprocurement.

One problem is that under 44 USC Chapter 31 and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) General Records Schedules (GRS), most federal contract records, including TDPs, are classified as temporary unless designated as permanent for historically significant programs. According to GRS 1.1, Item 010, most temporary contract records, including those with TDPs, are typically retained for about six or seven years after final payment.

For more complex contracts (e.g., defense or infrastructure), retention may extend up to 10 years. Once this period expires, records are often destroyed unless they are transferred to a federal records center or the National Archives for permanent retention.

For TDPs from contracts more than 10 years old, this order poses a significant risk of loss. Routine TDPs are rarely deemed permanent by NARA’s criteria, unlike records from major defense programs. Consequently, these TDPs may no longer exist if not flagged for archival retention during the contract’s active period.

In DoD contexts, DFARS 252.227-7013 (Rights in Technical Data – Other Than Commercial Products and Commercial Services) may require longer retention for TDPs if the contract explicitly specifies it or if the data is designated for archival purposes. However, the contract itself is pivotal – it serves as the government’s legal proof of ordering technical data, funding development work that generated the data and securing enhanced data rights, such as those for manufacturing (e.g., Register Transfer Level [RTL], Graphic Data System [GDS] or Process Design Kit [PDK] data for semiconductors).

If the contract is destroyed or not transferred to the National Archives, the government may lose its legal proof of ownership for critical technical data. Without this documentation, agencies cannot verify ownership or access to TDPs, even if the data was archived, severely complicating retrieval efforts for legacy systems or reverse engineering.

Another major challenge in this effort is the lack of robust data-rights provisions in historical DoD contracts. Many original agreements did not require OEMs to provide comprehensive technical data packages, leaving the DoD with limited access to critical information. It is now known that the industry needs improved contract language to secure DoD data rights and alleviate future complications. Contracts often lack explicit requirements for comprehensive TDPs, leading to gaps in documentation. To address this, the following clauses have been proposed to add to DoD contracts:

- Mandatory TDP delivery: Require OEMs to submit complete TDPs, including a copy of the data file for the mask sets, the foundry, and the process recipe used, as well as test protocols, as part of CDRLs.

- Data escrow provisions: Mandate that technical data be stored in a DoD-accessible escrow to prevent loss during OEM transitions.

- Licensing agreements: Include provisions for perpetual licensing of designs for DoD use, ensuring access even if OEMs cease operations.

These clauses would increase the DoD’s leverage, reducing data-recovery efforts and ensuring long-term access to critical information.

Cultural myths around reverse engineering

Another issue surrounding reverse engineering and reprocurement stems from cultural myths within the DoD ecosystem, where a widespread belief persists that it is off-limits or legally fraught. Nonresponsive OEMs are often viewed as the end of the road; however, reverse engineering is explicitly permitted under MIL-HDBK-115A, the U.S. Army Reverse Engineering Handbook. This document outlines guidelines for performing reverse engineering to enhance competition, stipulating that while patented items require government authorization, the process is viable when done correctly.

Many program managers (PMs) assume there’s “no way” due to misconceptions about intellectual property (IP) risks, but the Army handbook delineates the right way (e.g., with formal approvals and documentation) versus the wrong way (unauthorized copying). By creating a process dichotomy supported by sources like MIL-HDBK-115A and DoD’s Spare Parts Breakout Program, the goal is to inspire project managers to pursue alternative sourcing. The Spare Parts Breakout initiative, part of DoD’s acquisition strategy, evaluates items for competitive procurement, breaking out 20% to 30% of spares annually to reduce costs by 15% to 25%.

Dispelling these long-held myths involves training and policy advocacy, ensuring that reverse engineering becomes a standard tool for addressing supply issues, as recommended in the Defense Production Act, which leverages it for critical chains.

Leveraging MEBDW

A cornerstone of this manufacturing strategy is the multi-electron beam direct write (MEBDW) lithography system. Unlike traditional photolithography, which relies on masks and is optimized for high-volume production, MEBDW lithography was developed using 65,000 electron beams to directly pattern wafers. This process eliminates the need for costly masks while achieving throughputs far greater than those of a single beam.

These benefits make it ideal for flexible volume and high-mix production, which are needed for cost-effective legacy semiconductor manufacturing. MEBDW lithography’s lack of masks enables a purely digital process flow from inception to delivery.

The MEBDW lithography system offers several advantages for military applications, including flexibility, as it supports a wide range of process nodes (from 22 nm to 180 nm) accommodating a diverse portfolio of designs. The system can handle a range of wafer sizes, from 100 mm to 300 mm. It also enables rapid prototyping and quick iteration of designs, reducing development timelines; and cost efficiency, as it eliminates mask costs.

As the method is further developed as a drop-in replacement process for I-line lithography, DoD devices will be transitioned to using the MEBDW lithography system exclusively.

Toward an on-demand manufacturing platform

The long-term vision is to integrate MEBDW lithography with an AI-driven chip-design suite to create a platform for on-demand manufacturing. This platform would enable rapid transition of legacy and novel designs to production, reducing total cost of ownership (TCO) and enhancing supply chain security. The AI suite, which is in development using reverse-engineering projects as proof of concept, would:

- Analyze legacy data: Parse incomplete or fragmented technical data to generate complete design files.

- Optimize designs: Adapt legacy designs for modern processes while maintaining functional compatibility.

- Automate production files: Generate GDSII files (the data format used in chip and integrated circuit design) and process recipes for direct use in MEBDW lithography systems.

Such a digital-first approach would enable the DoD to produce small batches of legacy parts on demand, thereby minimizing inventory costs and reducing the risk of obsolescence. For military embedded systems, this capability ensures the continuous availability of components for critical applications, even as commercial foundries phase out older nodes.

In addition, the military is a strong point of market entry for MEBDW lithography, as it facilitates rapid development in commercial segments, such as AI, quantum, and the commercialization of novel technologies, thereby bridging an institutional void from research to high-volume manufacturing.

Lex Keen, the founder and CEO of SecureFoundry, has more than 23 years of experience leading military and dual-use technology programs. A former U.S. Marine Corps technologist and investigator, he served as Technical Director at U.S. Cyber Command and contributed to NATO’s Quantum Expert Group.

SecureFoundry • https://www.securefoundry.com/