Tactics to enable SWaP-C improvements in military thermal imaging

StoryMarch 18, 2025

Companies that build vision and guidance systems for night vision, uncrewed systems, and robotics applications are very familiar with the potential for long wave infrared (LWIR) thermal imaging to revolutionize defense and warfare. To support broad deployment of these cameras, improvements in performance and cost are needed. By applying the SWaP-C [size, weight, power, and cost] goals originally laid out for defense equipment, a camera meeting the stringent performance and cost requirements in new automotive safety systems has been developed. These new cameras can now be supplied into defense applications, bringing back the full set of benefits.

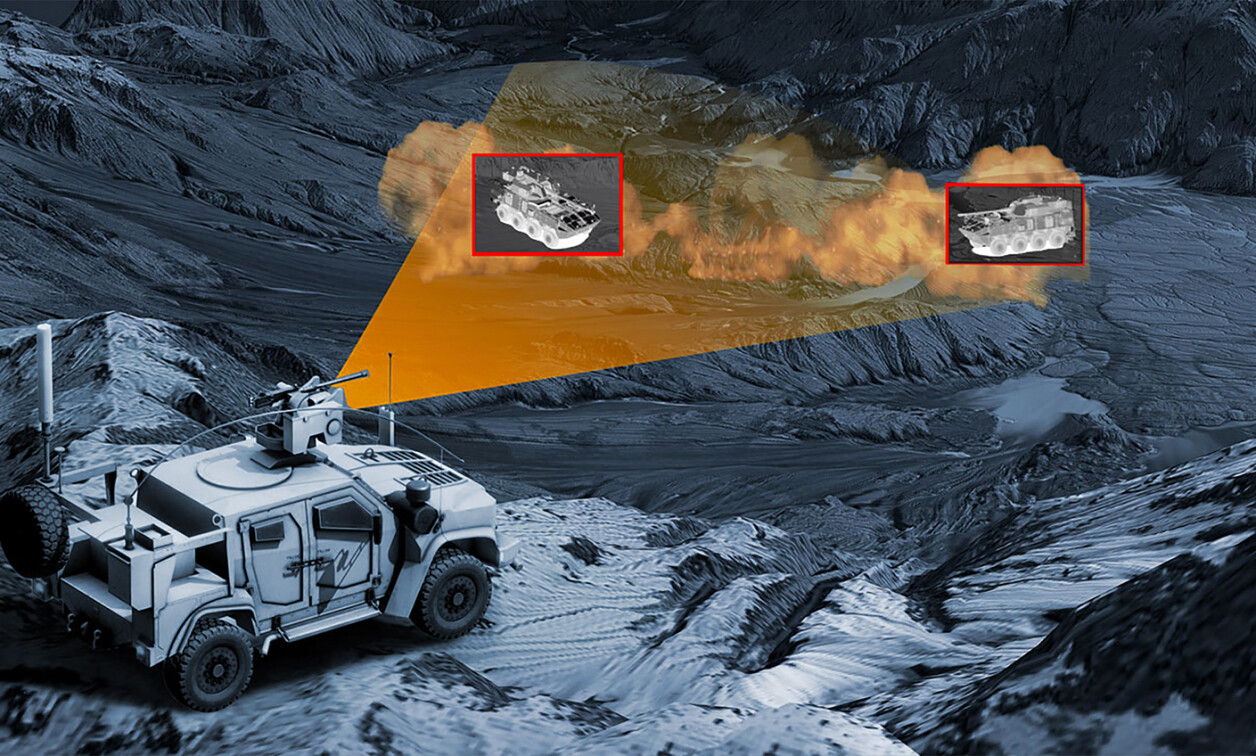

For more than 50 years, thermal imaging has been providing the warfighter with information on the location and type of personnel, vehicles, facilities at night and under obscured conditions as illustrated in Figure 1. In that time, thermal camera size and complexity have been drastically reduced by improvements in thermal and spatial resolution, relaxation of cryogenic-cooling requirements, and development of new thermal-sensing materials.

[Figure 1 ǀ Thermal imaging provides the warfighter with images of personnel and vehicles in day and night, under clear or obscured conditions.]

Even so, high-performance thermal cameras remain large and very expensive, while even small thermal cameras with limited capabilities still cost substantially more than their visible counterparts. Fortunately, improvements in other electronic equipment achieved through application of SWaP-C [size, weight, power, and cost] principles provides guidance to designers of new thermal cameras, producing the solution described here.

In the defense industry, the drive to reduce the size, weight, and power consumed by electronic equipment was labeled SWaP-C, with the “C” added to remind developers that even in defense programs, cost must be controlled. The result has been implementation of ever-increasing functional integration, in the quest to provide cheap, high-functioning computers, radios, and cameras.

However, thermal imaging has been more resistant to SWaP-C improvements, primarily because of the limited choices in sensing materials suitable for detecting thermal energy at room temperature.

Two detection methods are possible. The first, similar to the detection method for visible light, is the direct conversion of incoming photons into charge. In the visible and near-infrared bands (400-1000 nm) silicon can serve as the detector. In the thermal bands (3 to 5 µm and 8 to 14 µm) however, the photon detection material must have a much smaller bandgap to match the low energy of the photons. The most common material, HgCdTe [mercury cadmium telluride], works well but must be cryogenically cooled to control dark current (dark current is the relatively small electric current that flows through photosensitive devices even when no light is hitting it). Unfortunately, coolers are big, heavy, and expensive.

Starting in the 1980s, production models of arrays of miniature bolometers became available. Instead of capturing photons to liberate charge, bolometers convert received energy (of any wavelength) into a change in resistance. This process is not as efficient as photon detection and fails to produce acceptable signal-to-noise ratio in the 3 to 5 µm band (designated mid-wave infrared or MWIR). In contrast, in the long-wave infrared (LWIR) band (8 to 14 µm), microbolometers perform well so these detectors, which do not require cooling, have become dominant in the thermal-imaging markets.

For both HgCdTe and microbolometer arrays, the detector part is manufactured using special processes designed for handling the specific materials and configurations. Separately, a device called a readout integrated circuit (ROIC) is fabricated in silicon using standard production processes. The two devices are bonded together, typically with mating metal bumps, to produce a complete sensor.

For both arrays, the ROIC output is an analog signal representing the response of the array elements to arriving thermal images. These signals must be corrected for the ambient temperature of the detector and for nonuniformities in array response.

These corrections are most easily performed in the dark digitally, so the outputs of the ROIC must be digitized, an operation that takes place on circuitry outside the ROIC, and the camera must include a mechanical shutter that can be periodically closed for acquisition of calibration data.

Fortunately, an explanation of how current sensors are built suggests some relatively straightforward approaches to SWaP-C improvement, but why have they not been implemented? Simple answer: Producing semiconductor devices cost-effectively requires producing them at volume – not thousands or even hundreds of thousands, but millions or more. The existing markets were not nearly large enough to support the costs of custom sensor development or to absorb the quantities of sensors that would be produced.

Early in 2024, the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration came to the rescue when it issued a new rule which (starting in 2029) requires effective day and night pedestrian automatic emergency braking (PAEB) systems on all light vehicles. It has been repeatedly demonstrated that these systems will require thermal imaging to operate effectively at night or in situations compromised by rain or fog, so the justification for investing in SWaP-C improvements has become clear.

Here are the steps to be taken:

- Eliminate the need to bond two devices

- Provide an ROIC with a digital output

- Develop a shutterless method of calibrating the camera

- Reduce the need for auxiliary devices

- Meet the performance requirements for PAEB systems

Removing the technology constraints enables well-developed assembly processes to be applied to the production of thermal sensors. The most beneficial of these is the process set that enables design of fine-line, high-speed digital integrated circuits that comply with the -40 °C to +125 °C automotive operating temperature requirement that readily transfers to defense equipment.

A novel ROIC is now available that integrates a sigma-delta analog to digital converter (ADC) for each pixel which accepts both offset and gain non-uniformity correction (NUC) data. Because these corrections are applied during the digitizing process, the ROIC can supply 18 bits of corrected data per pixel at up to 120 Hz frame rates.

The correction data includes factory measurements of the sensitivity of individual microbolometer pixels taken over the entire operating temperature range, calibration data from the camera lens, and real-time temperature maps of the sensor substrate to assure that the proper correction is continuously applied without the need to interrupt the image flow with an external mechanical shutter.

Filling the ROIC with a pixel-sized array of ADCs reduces the necessary circuitry on the chip outside the active pixel area. The result, as shown in Figure 2, is that an ROIC area that formerly supported a VGA (640 by 480) array can now provide the 1280 by 800 resolution needed in the automotive industry. Further, the elimination of the surrounding circuitry permits the ROIC to be configured so that the microbolometer pixel array can be grown on its surface rather than bonded as a separate wafer, offering a substantial reduction in cost and improvements in yield and reliability.

[Figure 2 ǀ A digital ROIC with all control and correction circuitry fits neatly below the microbolometer array.]

Building a camera using such a sensor, as seen in the example shown in Figure 3, requires adding only power-conditioning circuitry and an interface chip. Because the ROIC has an internal controller, the sensor can be configured to refuse to operate until an enabling code is received. There is no enabling pin which might be discovered by an adversary, vastly improving the security required for use in military devices.

[Figure 3 ǀ A fully digital ROIC reduces the need for support circuitry to just power conditioning and interfacing.]

With a sensor like this, thermal cameras become suitable for deployment in small uncrewed systems with confidence that, if the craft is downed, camera repurposing is not possible. The SWaP-C improvements facilitate deployment in sights, security perimeters, vehicles, and even projectiles, thereby providing improved situational awareness to the warfighter.

Wade Appelman (Chief Business Officer at Owl AI) has held key leadership roles in both private and public-sector organizations. Wade helped launch SensL, a leader in single-photon detection used in LiDAR and medical imaging (acquired by ON Semi in May 2018). Subsequently, as VP and GM of ON Semiconductor’s depth sensing division, Wade led the team developing low-light sensors for early customers executing designs in automotive, medical, and industrial markets.

Owl Autonomous Imaging https://www.owlai.us/