Building a layered, aware PNT architecture for the modern battlespace

StoryDecember 05, 2025

The wars in Ukraine and the Middle East have turned the invisible battlespace of the radio spectrum into a front-line theater. GPS interference has evolved from isolated, tactical events into a persistent component of modern electronic warfare (EW), targeting navigation systems at every altitude and across every domain. For the U.S. and its allies, this is not a hypothetical concern or a future problem. It is a real-time operational reality, one that has exposed the fragility of GPS in ways decades of modeling never could. While there is no single substitute for GPS, there is a path to make it resilient, aware, and self-healing – this is the path to assured PNT in the contested battlespace of the 2020s and beyond.

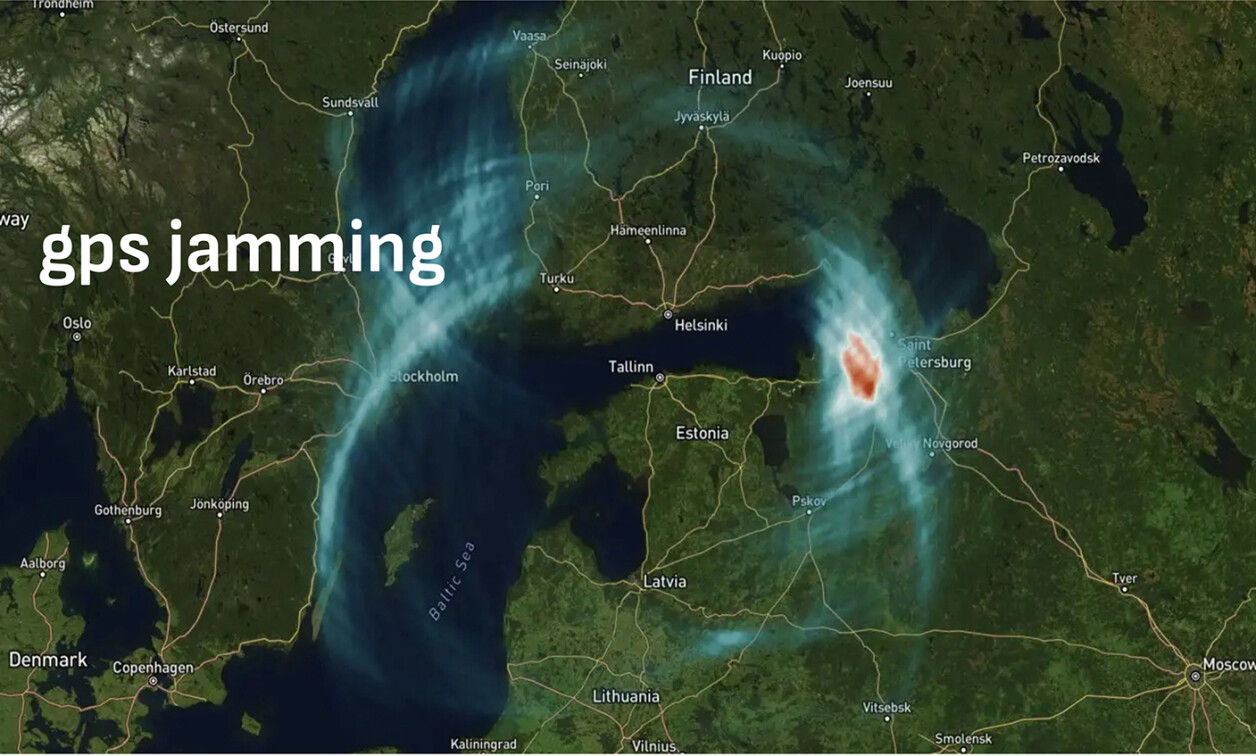

Russia’s sustained GPS-denial campaigns across Eastern Europe, widespread interference across Israel and Gaza, and Iran’s periodic spoofing operations in the Persian Gulf have shown how quickly and effectively GPS can be degraded in modern conflict. In each case, the attacks have not been static; they have evolved dynamically in response to countermeasures, forming an iterative loop between offense and defense.

In this new environment, assured position, navigation, and timing (PNT) is not just about maintaining accuracy, but about maintaining awareness. The U.S. military cannot protect what it cannot see. Understanding, mapping, and adapting to GPS interference in contested environments has become a mission-critical capability for every service branch and every platform.

GPS denial in the real world

In Ukraine, GPS denial has moved beyond isolated disruptions to what is now an industrial-scale part of modern warfare. Russian forces use layered jamming systems that range from small, tactical units meant to blind drones to powerful, wideband systems that can block satellite navigation across hundreds of kilometers.

In partnership with the Separate Service of UAV of the Ukrainian Volunteer Army, Zephr conducted extensive field tests to study Russia’s GPS interference operations under active combat conditions. These tests enabled collection of real-world data on how electronic attacks manifest in the field. The team deployed Android smartphones on static sites, vehicles, and drones to collect GNSS measurements, each running Zephr’s networked GNSS technology, which turns ordinary mobile devices into a distributed, high-fidelity sensing layer. Testing took place on the front lines near Donetsk and in other regions such as Odessa, where controlled experiments were carried out using Ukrainian jammers.

This field research shows that many GNSS interference detection and localization techniques, though well-established in academic literature, often fail under real-world battlefield conditions involving wideband jammers. Since no modulated signals are present to tune by a receiver, methods like time-difference-of-arrival (TDoA) require large, specialized networks of time-synchronized high-end correlators, operating at high data rates, which are expensive and impractical to deploy in a battlefield setting. In Ukraine, for instance, Russian systems often continuously saturate the full GPS L1/L2/L5 frequency ranges simultaneously and with uncorrelated noise, a tactic that disrupts all nearby GPS receivers. Even outside direct combat zones, lower-grade jammers can overwhelm conventional monitoring systems because of limited sensor coverage and technical constraints. The result is low-fidelity data and large blind spots, or “areas of effect,” where GPS disruption is happening but not being mapped in real time.

The findings show that Russia’s jamming in the field is broadband, powerful, and unpredictable. In several tests, the phones detected so-called ghost satellites – signals that appeared to come from satellites below the horizon. These false signals, often mistaken for spoofing, occur when wideband or pseudo-random noise (PRN) patterned interference overwhelms standard receivers. The result is confusion rather than deception, as the receiver’s navigation becomes erratic or collapses, rather than being lured to a false position.

This distinction matters for operations. When a drone or vehicle loses GPS because of jamming, it doesn’t just drift: it can crash, lose communication, or misreport its position. Understanding how that failure happens is key to developing countermeasures that can detect interference early and preserve partial functionality.

Altitude also proved to be a critical factor. In side-by-side tests, airborne receivers lost GPS fixes completely, while ground-based phones kept intermittent locks. This finding aligns with battlefield reports that drones are more vulnerable to saturation jamming, while forces and vehicles on the ground sometimes retain enough signal to navigate. For commanders, GPS reliability can shift dramatically within a few hundred feet of altitude, which is a critical factor for unmanned and air defense operations.

Across multiple test runs, jammed receivers showed sharp fluctuations in signal strength and noise, while static receivers farther away remained stable. These telltale patterns confirm that modern jammers are highly directional and terrain-sensitive, producing interference “hot zones” that follow valleys, ridgelines, or urban structures.

The overall lesson is clear: GPS denial on today’s battlefield is dynamic and adaptive, not static or uniform. Its impact shifts with terrain, altitude, and geometry to form irregular “volumes of denial” rather than simple circular bubbles. Clear-sky assets like aircraft and drones often suffer the worst degradation, while lower or shielded platforms may still operate, albeit with degraded precision. (Figure 1.)

[Figure 1 ǀ During field testing, networked GNSS technology was installed on phones, and data was collected both in controlled jamming environments with a friendly jammer and in an adversarial environment close to the front lines on drones, in vehicles, and on foot. Image courtesy Zephr.xyz.]

For military planners and engineers, that reality demands a new approach, one that is built on real-time detection, mapping, and adaptive mitigation. GPS denial is no longer just a threat to navigation; it is an evolving part of the electronic order of battle.

The next flashpoints: Asia and the Middle East

While Ukraine remains the most heavily documented environment for GPS denial, similar trends are emerging elsewhere.

In the Taiwan Strait and the broader Indo-Pacific region, Chinese forces routinely conduct gray-zone electronic warfare (EW) operations that test and map allied responses. Commercial airliners have reported intermittent navigation anomalies along key flight routes near Taiwan and the South China Sea. Firsthand reports assert that Chinese jamming is active throughout the Taiwan Strait, yet much of it remains invisible to outage maps that rely on internationally used ADS-B data. This invisibility occurs because many of these systems employ low-angle, terrain-shielded jammers designed to evade detection from aviation and orbital sensors. The result is an incomplete operational picture of interference activity in one of the world’s most strategically sensitive air corridors.

In the Middle East, GNSS spoofing is now a routine defense tactic used to shield critical infrastructure and mislead UAVs and GNSS-guided missiles. Israeli systems often employ proactive spoofing to obscure sensitive sites, while Iranian and proxy forces use similar methods to disrupt drone navigation. The result is a battlespace where legitimate and deceptive interference frequently overlap, complicating attribution and response. In a separate analysis, emerging “push spoofing” activity was documented in Haifa, Israel, where GNSS receivers were gradually displaced offshore rather than teleported to a fixed airport location. Unlike conventional spoofing, which is designed to trigger drone no-fly restrictions by faking airport coordinates, this new technique appears intended to manipulate flight paths or guidance systems in real time, signaling an evolution in EW tactics.

Collectively, these theaters illustrate that GPS denial is no longer an episodic threat. It is a constant feature of modern warfare and a controllable variable in every commander’s electronic order of battle.

The U.S. challenge: operating blind in the spectrum

Despite decades of warnings, the U.S. still lacks a fully integrated, high-resolution system for detecting and mapping GPS interference in real time. Current detection relies primarily on a mix of satellite sensors, ADS-B reporting from aircraft, and localized ground receivers near major installations. This approach leaves enormous blind spots, particularly at low altitudes, where most tactical operations occur.

Many of the strongest jammers in Ukraine operate below the detection threshold of ADS-B-based systems because they are terrain-masked or configured for low-angle propagation. From a high-altitude sensor’s perspective, these jammers simply disappear.

Without comprehensive domain awareness, military operators face two simultaneous challenges: First, they cannot precisely characterize where and how interference occurs; and second, they cannot localize the emitters fast enough to target or avoid them.

The U.S. needs a persistent, automated means of detecting and localizing GPS jamming and spoofing that integrates space, air, and ground sensors with edge devices operating in the field.

Lessons from the field: toward a distributed detection grid

One of the most promising approaches is also one of the simplest: Use the assets already deployed in the battlespace as sensors.

Modern handhelds are equipped with GNSS receivers capable of capturing the raw observables needed to detect anomalies. When these measurements are networked and aggregated securely, or even intermittently, they can be fused to produce real-time interference maps with far greater resolution than any fixed infrastructure.

During Zephr’s testing under an Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL) program (which includes field testing in Ukraine as well as multiple U.S. military exercises), mobile devices are configured to detect and classify GNSS jamming and spoofing while estimating the area of effect for each event and geolocating emitters in the field. This testing shows how rapidly and granularly interference can be mapped when devices collaborate across a broad region and different altitude layers.

This type of distributed detection offers a scalable path forward. By treating every fielded device as a potential sensor, the military can create an adaptive mesh network for PNT situational awareness. The data doesn’t need to stream continuously; even sporadic uploads can feed central fusion engines that alert operators when anomalies exceed threshold levels.

Ultimately, this model transforms interference from an unseen hazard into an observable variable, which is the first step toward true EW domain awareness for GPS.

Understanding AltPNT: options and limitations

At the same time, the U.S. military is investing in alternative positioning, navigation, and timing (AltPNT) technologies. These range from inertial systems and signals of opportunity to terrestrial radio networks, low Earth orbit (LEO) satellite constellations, and quantum sensors. Each contributes valuable redundancy, but none is a turnkey replacement for GPS.

- Inertial navigation systems (INS): INS remains the most reliable short-term backup for GPS, particularly when tightly coupled with PNT filters. However, even advanced ring-laser and MEMS-based systems accumulate drift without external updates. Emerging “quantum” INS technologies promise dramatic drift reductions, but they still require a known starting coordinate to function, which means they cannot bootstrap absolute position without another reference.

- eLORAN: Long-range terrestrial radio systems like eLORAN offer resilience against jamming due to high signal power and low frequency, but they are infrastructure-intensive and regionally constrained. They also provide only lateral positioning, not altitude, which limits their standalone utility for air operations.

- LEO PNT constellations: Commercial satellite providers are developing LEO constellations that can deliver faster, stronger signals and lower latency. However, because LEO satellites move rapidly, global coverage requires hundreds of spacecraft, extensive ground infrastructure, and constant handoffs. While these constellations will improve redundancy, they still rely on ground-control links and are vulnerable to electronic and kinetic attack, making them a complementary (not a replacement) layer for military PNT.

- Terrain and Visual Navigation: For aircraft and autonomous systems, terrain-referenced navigation (TRN) and vision-based systems provide valuable drift correction when GPS is degraded. However, both depend on stable, premapped environments. In rapidly changing combat zones – or in regions obscured by dust, smoke, or debris – these systems can degrade or fail altogether.

The takeaway is clear: There is no silver bullet. Every AltPNT option offers situational value, but each carries environmental, operational, or logistical constraints. Resilience will come from combining them intelligently and knowing when to trust each layer.

Why a layered PNT strategy is essential

A layered PNT architecture recognizes that every method of determining position or time has a failure mode, and that those failures can often be compensated by cross-referencing others.

The core principle is graceful degradation: as interference increases, the system dynamically shifts its weighting among available inputs. A distributed, ground-based network of mobile receivers provides early warning of interference, creating the first layer of situational awareness. When GPS confidence drops, INS and visual systems carry more load; when those drift, terrestrial or cooperative positioning adds correction; and when all degrade, the system communicates its uncertainty clearly to operators and higher-level networks.

For embedded systems, the challenge is less about hardware and more about software adaptability. Filters must be able to reconfigure in real time, ingest external cues such as interference maps, and adjust behavior based on context. Modern data architectures, including edge-based artificial intelligence (AI) and secure cloud synchronization, make these goals increasingly achievable even in constrained environments.

In practice, a layered approach also means fusing domain awareness with navigation itself. A warfighter’s device should not just display a coordinate; it should communicate confidence and show why that confidence has changed.

When operators can see the electromagnetic battlespace as clearly as the physical one, they can adapt tactics accordingly, choosing alternate routes, timing operations around interference cycles, or directing fires to suppress emitters.

Building true EW domain awareness

Electronic warfare domain awareness must go beyond detecting interference to transforming signal disruptions into actionable intelligence. A comprehensive architecture would integrate multiple layers of sensing and analysis:

- Space-based assets to observe large-scale jamming and track persistent interference patterns.

- Airborne platforms (manned and unmanned) to fill mid-altitude gaps and provide angular diversity.

- Ground and mobile sensors to capture localized signal degradation, spoofing patterns, terrain effects, and geolocation of emitters.

- Edge analytics on tactical devices to identify anomalies in real time, even under degraded connectivity.

- Central fusion services to combine these inputs into live maps of interference intensity, confidence, and probable source location.

Such a framework would allow commanders and engineers to understand not just where GPS is being denied, but why, how, and by whom. It would also enable faster countermeasures, from rerouting assets to retasking sensors or targeting emitters.

Developing this capability requires close collaboration between the services, research agencies like AFRL, and private industry.

Engineering for the contested spectrum

For system designers, integrating EW domain awareness and layered PNT into embedded platforms presents several practical challenges:

- Access to raw GNSS data: Many receivers abstract or discard observables needed for interference detection. Future designs must expose this data securely to onboard software layers.

- Computation at the edge: Embedded processors must run lightweight detection algorithms without compromising mission software. Efficient, hardware-agnostic implementations are key.

- Intermittent connectivity: Systems should queue and forward interference data opportunistically, maintaining function even when disconnected.

- Latency and synchronization: Shared PNT and EW data must remain time-aligned to enable triangulation and emitter attribution.

- Cybersecurity: Any distributed detection framework must be hardened against spoofed reports and hostile data injection.

Together, these challenges highlight the need for common PNT interfaces and modular architectures that can evolve with the threat environment.

The way forward

The wars of the past three years have made one fact unavoidable: GPS is no longer assured by default. Every contested environment – whether in Europe, the Pacific, or the Middle East – now features deliberate, adaptive attempts to deny or deceive satellite navigation.

The U.S. cannot afford to be reactive. We must evolve from viewing GPS as a standalone service to treating it as part of an integrated, adaptive PNT ecosystem. That ecosystem will blend global satellite signals with regional terrestrial aids, cooperative mobile sensing, open environmental corrections, and continuous EW domain awareness.

Field data from ongoing programs, including those supported by AFRL, demonstrate that evolution is achievable using existing hardware and modern software architectures. By transforming every device into both a user and a sensor of PNT, the military can build a resilient foundation for operations in any spectrum environment.

Sean Gorman, Ph.D. is the CEO and co-founder of Zephr.xyz, a developer of next-gen precision positioning and AI navigation agents. Gorman has a more than 20-year background as a researcher, entrepreneur, academic, and subject-matter expert in the field of geospatial data science and its national-security implications. He is the former engineering manager for Snap’s Map team, former chief strategist for ESRI’s DC Development Center, founder of Pixel8earth, GeoIQ, and Timbr.io, and held other senior positions at Maxar and iXOL. Gorman served as a subject-matter expert for the DHS Critical Infrastructure Task Force and Homeland Security Advisory Council, and holds eight patents. He is also a former research professor at George Mason University.

Zephr.xyz • https://zephr.xyz/